Two Key Factors Affecting Heat Pump Efficiency: Temperature Difference & System Optimisation

Heat pumps are among the most efficient technologies for thermal energy transfer in both heating and cooling applications, and there are key factors affecting heat pump efficiency. This article discusses a critical factor influencing heat pump efficiency and energy consumption.

The performance and efficiency of heat pumps are affected by numerous variables; unlike lighting systems, they cannot be represented by a single fixed efficiency value. Instead, efficiency varies significantly depending on a combination of technical, environmental, and operational factors. Understanding these influences is essential for engineers involved in system design, installation, and optimization.

Heat pump efficiency is most commonly measured by the Coefficient of Performance (COP), defined as the ratio of useful heating or cooling output to the energy input. A higher COP indicates greater efficiency. However, COP is not a constant value—it is sensitive to various parameters discussed throughout this section.

Below is an overview of a key parameter, Source–Sink Temperature Difference, affecting heat pump performance and efficiency, particularly the Coefficient of Performance (COP), Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio (SEER), Heating Seasonal Performance Factor (HSPF), and related metrics.

Key Factors Affecting Heat Pump Efficiency: Temperature and Temperature Difference (Source–Sink Temperature Difference)

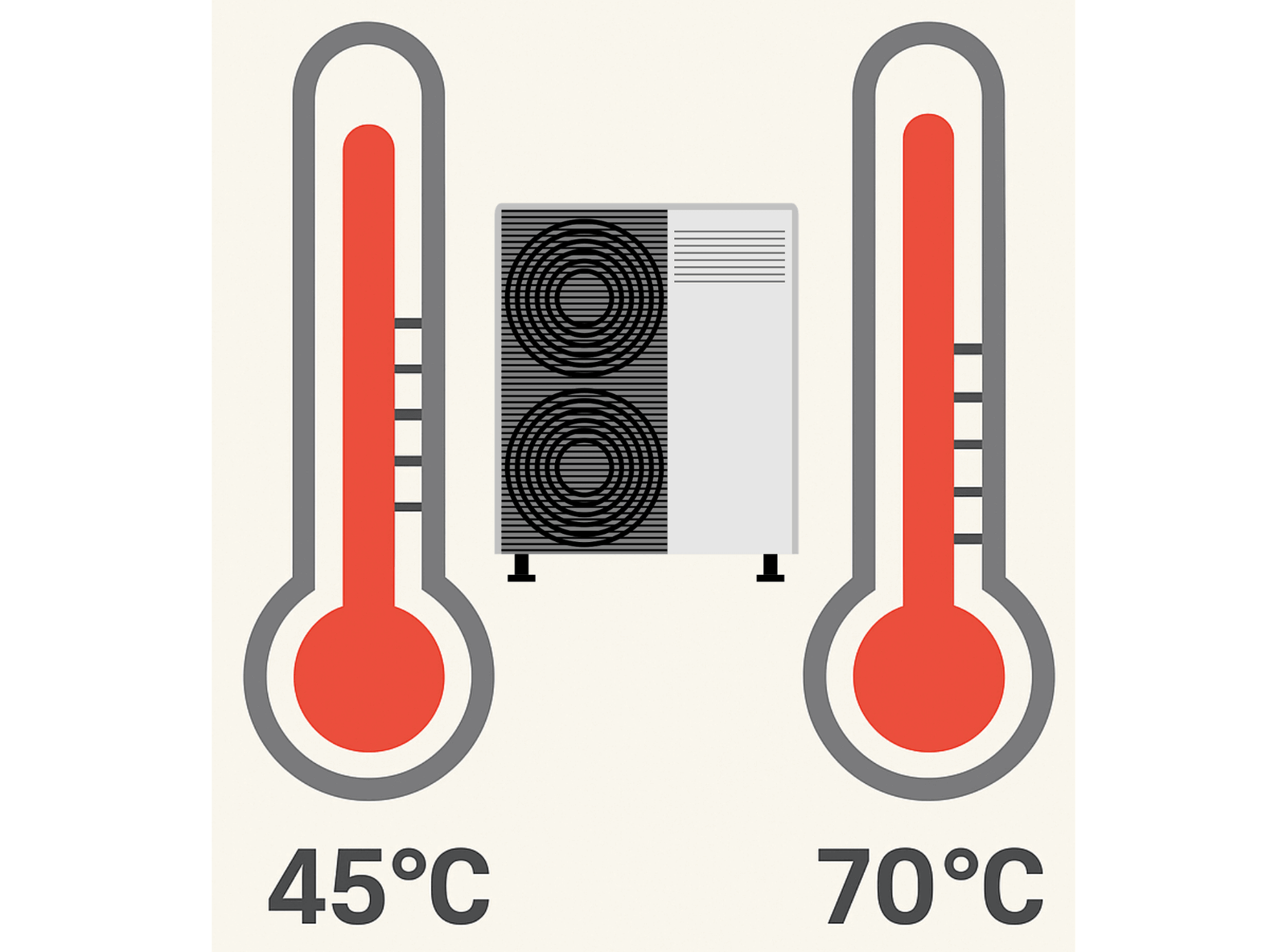

The efficiency of a heat pump varies depending on the required temperature level of operation. As the temperature difference between the heat source and the heat sink increases, efficiency decreases for the same amount of energy. This temperature difference—often referred to as the “temperature lift” or “approach temperature” on each side—directly affects the compressor workload and overall cycle performance.

In thermal energy systems, temperature difference is the potential that drives heat transfer. While a larger temperature difference facilitates heat transfer between the working fluid and the heat transfer medium, it also necessitates lower suction pressure in the evaporator and higher discharge pressure in the condenser, which increases energy consumption. In essence, temperature—and the corresponding pressure adjustment—is the key parameter directly influencing energy consumption.

- Low Temperature Lift (10–20°C): COP values of 4.5–8 can typically be achieved.

- High Temperature Lift (>40°C): Depending on the refrigerant and compressor type, COP may fall to 2–3.5 or even lower.

The absolute temperature level is also a crucial factor. For example, heating an environment from 5°C to 35°C requires significantly less energy than raising the temperature to 65°C for an industrial process. Moreover, even when the temperature difference is the same (e.g., increasing from 55°C to 65°C versus from 65°C to 75°C), energy consumption differs because the quality (or grade) of heat at 75°C is higher than at 65°C.

The same principle applies to cooling: for the same cooling capacity, achieving a lower target temperature requires more energy. This explains why, in heating mode, reducing the target temperature, and in cooling mode, increasing the target temperature, improves efficiency. Hence, operating an air conditioner at 23°C instead of 18°C in cooling mode leads to better energy efficiency due to the difference in temperature level (quality). In heating, higher temperatures correspond to higher quality, while in cooling, lower temperatures represent higher quality.

Example of Temperature Quality (Grade) and Temperature Difference

Model | Heat Source / Heat Sink | COP |

Model 1 | 18/8 → 40/55 | 3.6 |

18/8 → 50/65 | 2.7 | |

Model 2 | 18/8 → 40/55 | 3.6 |

18/8 → 50/65 | 2.8 | |

Model 3 | 18/8 → 40/55 | 3.7 |

18/8 → 50/65 | 2.9 | |

Model 4 | 18/8 → 40/55 | 3.8 |

18/8 → 50/65 | 3.0 |

As illustrated in the Table, COP values are presented for four different heat pump models operating at two different temperature levels. Each model shows COP values for 40/55°C and 50/65°C conditions, corresponding to a 15°C temperature difference. Although the equipment and operating conditions are identical, efficiency decreases at higher operating temperatures. This demonstrates how operating conditions influence performance.

For instance, if a space is to be heated to 23°C, both temperature regimes could technically be used. However, according to the COP values in the table, the 40/55°C regime is approximately 20% more efficient than the 50/65°C regime. Therefore, designing systems to operate at such efficient parameters can yield significant energy savings.

In heating systems, the maximum achievable outlet temperatures of heat pumps (e.g., 75°C, 90°C, 120°C) can generally be attained much more easily with boilers. Moreover, boiler efficiency does not vary as drastically with temperature as that of heat pumps. Consequently, in facilities where the heating system is designed for higher temperature regimes (e.g., 90°C), integrating a heat pump for energy efficiency or energy transition purposes can be challenging.

Even if the heating load remains the same, the heat pump may struggle to reach the designed temperature level (e.g., 90°C). Higher temperature means higher energy consumption for heat pumps. Therefore, replacing a boiler with a heat pump in such cases is not always straightforward. The main reason is that heat pumps operate less efficiently, therefore consume more energy to cover the investment cost. Hence, the energy transition projects end up with high ROI. To ensure efficient operation and better ROI, not only the heat source (boiler) but also the design temperature and any dependent equipment must be modified accordingly. The system must be re-evaluated as a whole, which may increase investment costs.

Hence, system operating temperatures and design parameters should be determined within the optimal operating range of heat pumps. Doing so ensures lower energy consumption and higher overall system efficiency. There are various ways to optimise with budget efficiency.